The Case Background

Recently, I worked with a travel tech company. The platform allows property owners to list and distribute their properties to short-term rental marketplaces. The domain is irrelevant. What matters is this: I’ve seen the same structural patterns in completely different environments. Approvals without clarity. Assumptions without data. Solutions discussed before constraints are understood. Different industries. Same questions.

The questions in brief

- A feature is approved. What’s next?

- Our funnel is declining. What can we do?

- Releases are delayed. What’s your proposal?

When a Feature is Approved

In this case, the executive team approved a new feature: dynamic pricing based on seasonality and local events. The intention was clear: help hosts remain competitive and increase their revenue. However, approval does not automatically translate into clarity. Approval is momentum. Clarity is work. Before writing a single line of code, I revisit the problem. I want to understand its shape. How often does this actually happen? Who is really affected? Is the friction constant or occasional? What are hosts already doing today? I usually start with a small research cycle, analytics review and conversations with users; nothing heavy, just enough to see whether the pain exists the way we describe it, and whether it’s frequent or expensive enough to justify intervention.

Research should answer questions like:

- How often do hosts manually change prices?

- Do price changes correlate with higher bookings or revenue?

- What tools are they already using to calculate prices?

- Is this a control problem or a confidence problem?

- Do power users behave differently from casual hosts?

The answers tend to narrow the problem. Not everyone needed “dynamic pricing.” Some hosts were already adjusting prices manually. Others weren’t touching them at all. So the question slowly shifted from “build dynamic pricing” to “what exactly are we helping with?”

Bias Toward Lightweight Solutions

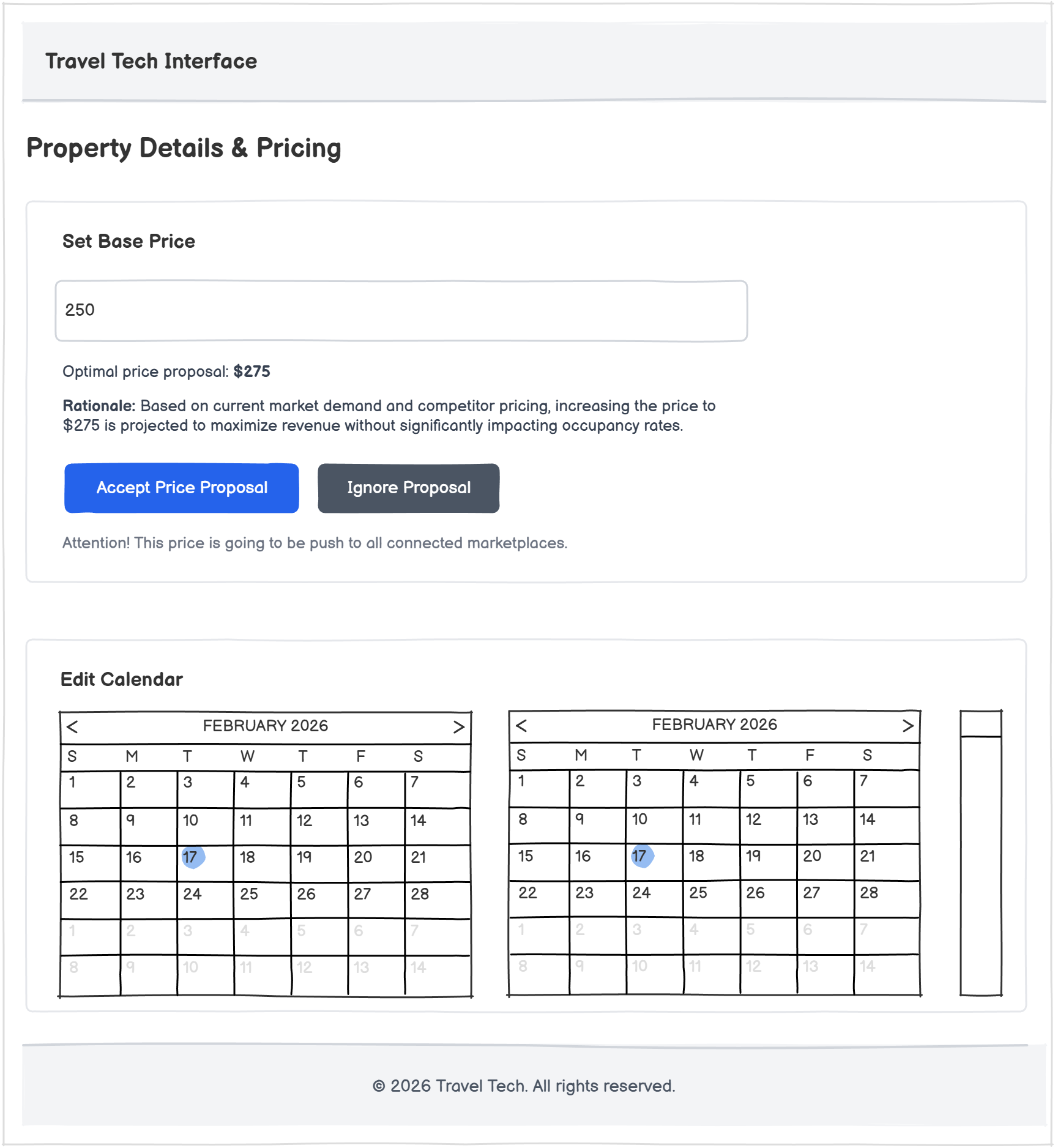

I rarely jump into defining the full solution. That’s prone to failure by definition, and not my job anyway. Solutions are shaped with engineering. My role is to make sure we’re solving the right problem and keeping it lean without adding complexity too early. Lean doesn’t mean simplistic. It means reversible. It means something we can learn from. If we were to build something at this stage, it would probably look like a thin decision-support layer:

✅ What to build

- Simple pricing optimization model + guardrails

- Basic manual event calendar

- Recommended price

- Short rationale

- Accept and Ignore buttons

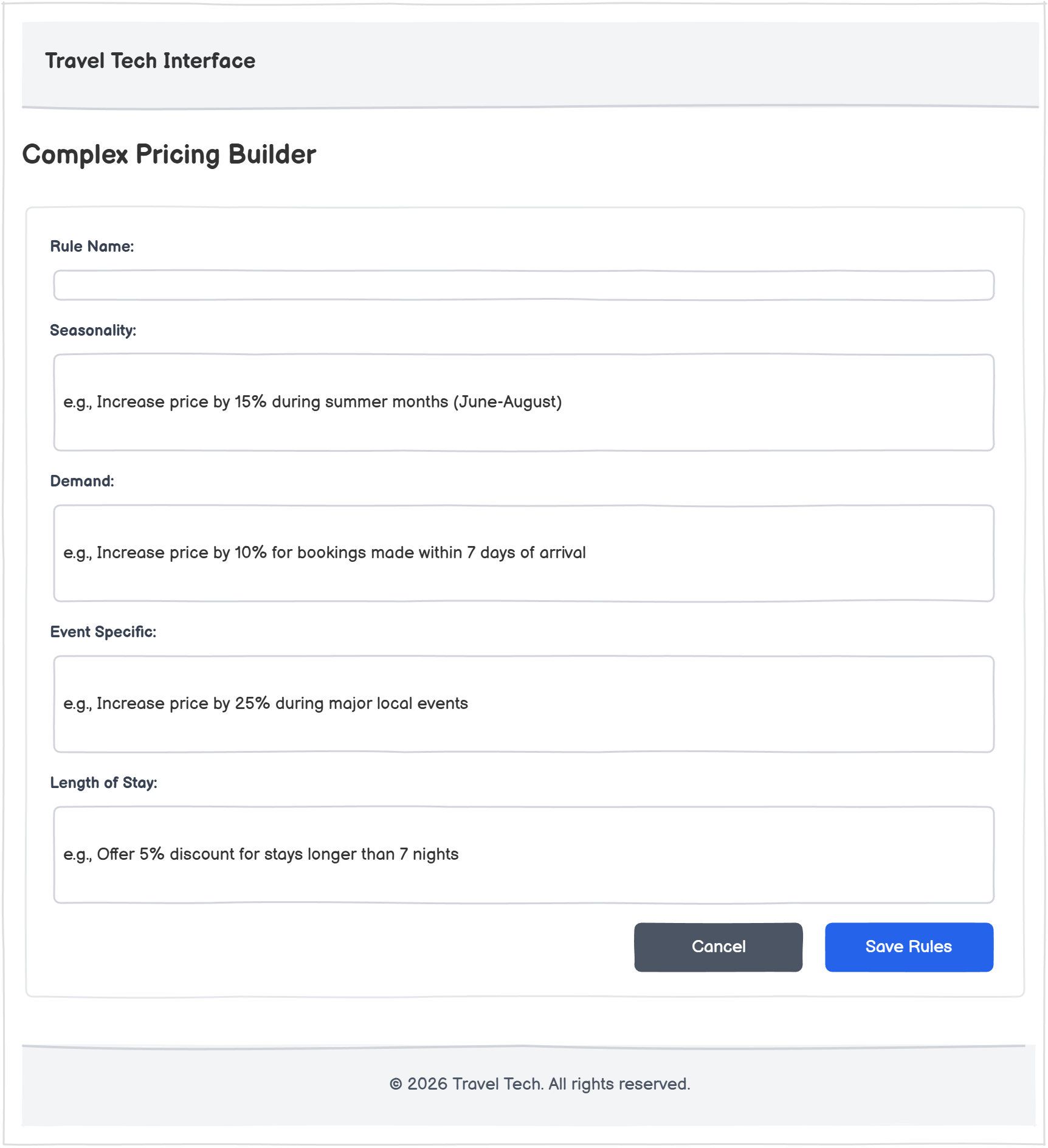

❌ What NOT to build (YET)

- Well trained AI pricing optimization models

- Event scraping engines

- Complex rule builders

- Automatic price push logic

- Heavy marketplace integrations

Why do I cut the builder? Not because it’s fundamentally wrong as an idea. But because we don’t yet know enough to justify the decision. At this stage, we’re observing behavior. If we introduce too much sophistication too early, it becomes difficult to tell whether the feature is working or whether we’re just adding movement.

What we don’t know yet

- We don’t know if hosts override recommendations.

- We don’t know if confidence is the real bottleneck.

- We don’t know if the issue is actually visibility, rather than pricing.

Success is defined upfront

Shipping something is progress. It’s not necessarily success. Before building, I prefer to define what “better” would mean in concrete terms. In our case, I would track the following performance indicators. This is not a performance theater exercise, just as a way to reduce ambiguity later.

Key Performance Indicators

- Feature Adoption [% of hosts who interacted]

- Recommendation Acceptance Rate [% Accepted vs Ignored]

- Conversion Rate [Listing View → Booking Confirmation]

- Revenue Uplift % + Empty days count [Control vs Target group]

- Pricing support tickets

Rollout is part of the feature

Once goals and metrics are aligned, the development team translates the idea into technical requirements. Which APIs, what contracts, what edge cases matter now? What stays out of scope? We break the work into small, possibly shippable increments, pieces that could go live independently. We add them to the roadmap even if we choose not to expose them immediately.

An ideal rollout plan

- Staging with internal users

- A handful of pilot hosts

- Feature flags (5% → 25% → 50% → 100%)

- KPI monitoring

When the Booking Funnel Drops

In this case, bookings were declining and users were describing the flow as “cumbersome”. “Cumbersome” is one of those words that can burn three months of engineering time if you’re not careful. But before redesigning anything, I prefer to locate the friction. First we define the flow clearly: Listing View → Checkout → Payment → Confirmation. If something is off, it usually happens somewhere specific.

I Look at the Signals

I start with the conversion rate by step, segmented by device, country, and acquisition source. Then I look deeper: time to complete, payment error rate, core web vitals. If available, session replays and heatmaps help connect numbers to behavior. If volume exists, the data tends to narrow the issue. If it doesn’t, I rely more on qualitative input. Five to ten conversations with recent bookers and recent abandoners are usually enough. Support tickets often add context. Sometimes a simple post-abandonment “What stopped you today?” email provides more clarity than a redesign workshop.

I Benchmark Competitors

At the same time, I review competitor funnels. Not to replicate them, but to understand where we might be missing something. I capture screenshots, record short flows, and compare them across a few basic dimensions

| Criteria (Score 1-5) | Our App | Competitor A | Competitor B | Competitor C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steps & friction | ||||

| Price clarity | ||||

| Sense of trust | ||||

| Payment experience | ||||

| UX & performance |

Explaining the table’s criteria, I look at the number of steps and the field count. Whether guest checkout exists. How clearly cancellation terms and fees are presented. What trust signals are visible. Which payment methods and currencies are supported, how errors are handled, and whether performance or accessibility might be adding unnecessary cognitive load. Most booking funnels don’t require innovation. They require friction to be removed.

When Delivery Slips

The third scenario was about repeated delivery delays in an Agile context. Some would argue this isn’t Product work. In many organizations, this would sit with an Agile Coach or a Scrum Master. But since this was a consulting engagement, I stepped in. Agile is not the point. Flow is. In my experience, delays are rarely about individual performance. More often, they are signals that the system needs adjustment. I don’t treat Agile as a ritual to defend. It’s a set of principles. When deadlines slip repeatedly, I assume something in the flow is misaligned, like faulty expectations, scope, clarity, or capacity. So the first step is to make the reasons for delay visible.

Starting with Baselines

Before changing anything, I run a working session around a simple question: “Where do we lose time and why?”. Tech and delivery leads bring the metrics they already track and explain how they interpret them. Without shared baselines, improvement conversations quickly become subjective. The goal of the session is not to redesign the process. It’s to agree on two or three measurable improvements and define a small experiment around them.

Typical metrics we examine

- Time to delivery (Lead time + Cycle time)

- Predictability (% Delivered vs Committed)

- Blocked time (Waiting for dependencies)

- Rework rate (Tickets reopened after delivery)

- Context switching (Too much WIP = Slower delivery)

My Bias Toward Clarity and Focus Protection

Across teams, certain patterns tend to repeat. Unclear tickets slow everything down. This is not solely a Product issue. Each team develops its own rhythm around ticket quality. Some operate well with lightweight descriptions and strong collaboration. Others require more detailed specifications. The important part is consistency. Excessive parallel work also affects delivery. Context switching is rarely visible on a dashboard, but it accumulates. Two tasks that should take two hours each rarely take four hours when handled in parallel. Mid-sprint scope changes have a similar effect. Even in structured sprint environments, urgent requests appear. Without clear boundaries, predictability erodes quietly. In these cases, I usually focus on a few fundamentals

The fundamentals

- A clear Definition of Ready (Let the team to decide this one)

- Weekly refinement with engineering and design

- Reasonable WIP limits

- Capacity-aware planning

- A Definition of Done that includes tests, tracking, and release notes

Stakeholder Alignment is Part of the System

Delivery slips are sometimes perception issues as much as process issues. One practice that has worked well for me is a lightweight product newsletter. A short, regular update shared with stakeholders. Not a presentation. Not a dashboard. Just context. When stakeholders understand the current state and the trade-offs involved, urgency becomes more grounded. Noise decreases. Conversations become more constructive. And often, delivery improves without changing much else.

The magic email includes

- Roadmap (Now/Next/Later)

- Key risks

- Decisions taken

- Initiative status indicators (Green/Orange/Red)

- Links to PRDs and decision logs for those who want details

Epilogue

If you strip away the industry specifics, the tools, and the rituals, product work tends to revolve around the same tensions. Clarity competes with speed. Signals compete with noise. Ambition competes with focus. A feature approved too quickly often turns into unnecessary complexity. A funnel redesigned too early risks becoming theatre. A delivery process defended blindly turns into ritual. The pattern repeats across environments, regardless of maturity or domain. What changes is the surface. What stays constant is the structure underneath. Over time, I’ve realized that most product problems are not solved by adding more frameworks. They are solved by asking better questions, sequencing decisions carefully, and protecting clarity before momentum takes over. Different companies will always have different constraints. But the structural questions remain surprisingly similar. Most of the time, the work is not heroic. It’s systematic. If I compress everything above into a simple operating logic, it would look like this.

The pattern, summarized

- Validate before building the solution

- Define what “better” means before writing code

- Ship in small, observable increments

- Make bottlenecks visible

- Improve systems before questioning individuals

- Protect team focus deliberately

- Communicate context, not just status